Murals offer a quick and dirty way to introduce a school to the joys of mud. Unlike play sculptures and benches, they require no foundation, minimal prep, and not much mud, either.

Murals offer a quick and dirty way to introduce a school to the joys of mud. Unlike play sculptures and benches, they require no foundation, minimal prep, and not much mud, either.

The typical approach to murals demands a narrative theme — on my first one, I suggested “creation and the four elements” (we were working with earth, air, fire (sun), and water, after all…).

It worked fine with the kids, who made something that looked much better than the industrial brick wall under it. Some parents got a bit worked up, but by the time I heard about it, a creative volunteer had welcomed them to teach an impromptu unit on comparative religion.

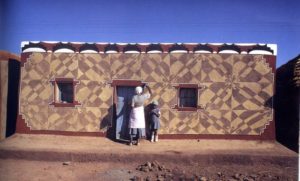

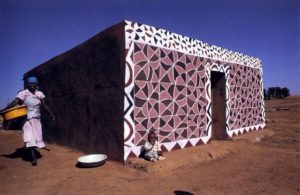

On the next mural I took inspiration from the women of Basutholand in South Africa, whose work I’d seen in the book, African Painted Houses, by Gary Van Wyk (these two photos are his, from the book).

Rather than propose a theme, I simply asked the kids to abstract geometric designs from their own drawings of local flora. Then I chose a handful of designs to assemble into a composition that we put on the wall. The process was as simple as the meaning, which came down to the kind of hospitable welcome flowers offer to anyone nearby – and forcing no one to accept a single interpretation of our multi-faceted universe. The result was nearly as beautiful as the plants and flowers that inspired it.

For the women of Basutholand, such murals hold a central place in a long-standing spiritual tradition. Home, and the spaces around it, make sacred vessels that contain and nurture us the way a mother’s dark, enclosing womb nurtures her child. The murals tell a story about how human culture marks the land. In the Basutho language, you don’t say a people are civilized, you say that their land “has lines on it’s face†– that it shows the marks and patterns of working humans who claim their place to satisfy their needs. As the earth answers our work and washes away our marks in an annual cycle of rain and wind, so does it wash away the murals, the making of which becomes an annual rite of renewal and re-connection.

The Basutho example not only offered a unifying theme that avoided divisive questions about “teaching religion in schools,†it also offered potential solutions to two other problems with making art in schools. The first one revolves around the tenuous place of the arts in school curriculae. By treating them as ancillary to reading, math, and science, schools deny Aristotle’s truth that “what we learn to do, we learn by doing.†Murals and other large-scale art projects, however, focus the entire community on a theme common to all, and provide a golden opportunity to crystallize individual lessons by shaping them into a shared story.

Student can work out design ideas and get familiar w/materials by working on a scrap of sheetrock — which they can take home.

The second problem is that art creates storage and maintenance problems. The substantial physical products of student work either have to be small enough for students to take home, or “good†enough to warrant a permanent spot on a wall and a long-term allowance in the annual maintenance budget. But it’s easy to convince most people that murals made of mud will be not only beautiful, but also impermanent, easy to “wash away,†and low-maintenance. Experience proves these to be true. The murals age well. The more exposed ones wear away slowly under the action of wind and rain or little fingernails, until it’s time to wash them away – and then they’re simply gone.

The greatest opportunity of such murals, however, poses challenges and rewards much greater than “teaching religion.†By far the greatest success would be to transplant the arts into the perennial culture of the school by making of them an annual rite, like the Basutho renewal of their house murals. Many schools make a rite of annual sports events or annual class trips or (in Oregon, at least) what they call “outdoor school,†whereby a whole class takes a week at the end of the year to go camping. By making an annual rite of removing and re-making a mural, schools could substantially enrich their local culture. Those who made last year’s mural would train and assist a new team the next year. The entire school could be involved in refining, re-defining, or re-envisioning a theme. Teachers could build enthusiasm and energy for the event by adapting their other curriculae to the shared subject. Students would become teachers, and all would share in developing a local tradition based on real skills and knowledge. And there would be far fewer divisive questions about committing the entire community to one permanent and eternal piece of art because every year would provide a new group the opportunity to tell the same story in their own way. And finally, the matter and spirit of the earth itself would take its rightful place as both source and symbol of eternal renewal. Old mud can be made new simply with the addition of water. Or it can be returned, usefully and joyfully, to the ground out of which it came. Either one would celebrate, beautifully, the same, essential truth.

here’s a gallery of murals; click on the thumbnail to see the entire photo:

This site is very elegant, as well as inspiring. The simplicity of designs any untrained teacher can use with the assurance of success and good taste. What I like is that you don’t need an artist to lead you. any mud molder can create a handsome mural if it is kept very simple and repitition of form is captivating as we see in the African designs.

Bravo Kiko the teacher of simplicity.

Wow! This article is amazing. Your images of kids doing art in schools are so inspiring. And to think that the materials they are using are cheap or free and non-toxic – that’s great. There’s such power to the contrasting colors and repetitive patterns. This post seems like a good start towards being able to offer a framework and suggestions for teachers at other schools who want to do similar work.